Stepping Stones to Suffrage

The Struggle for the Vote

Without the vote, women had to convince men in power to give it to them. Sound easy enough?

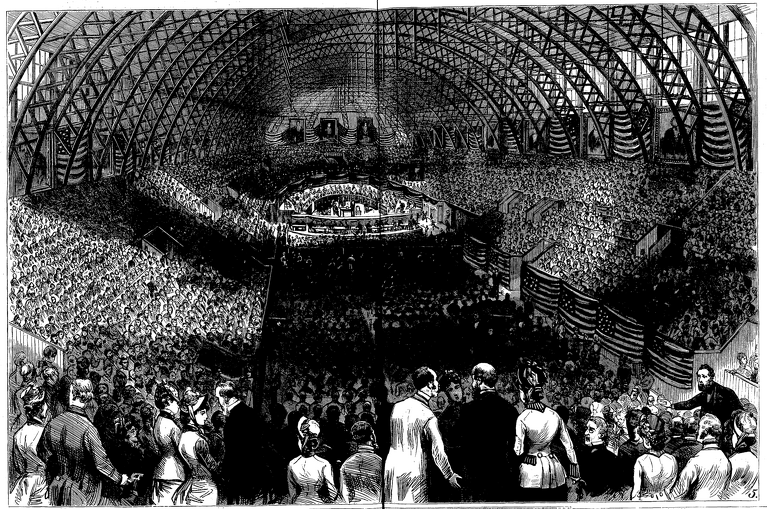

Year after year, activists traveled to Washington, DC, to persuade lawmakers to back a women’s suffrage amendment. At presidential election-time, they attended national party gatherings—such as the 1880 Republican National Convention in Chicago—seeking support for women’s rights. But without voting power, women faced an uphill battle getting politicians to back their causes. Whether they pressed for voting rights or other reforms, what difference would it make if these men just ignored them?

During the decades before Congress passed a federal suffrage amendment in 1919, Chicago women of different backgrounds pursued varied goals—working to reform society, achieve economic and political empowerment, and promote racial equality. Those issues and efforts also propelled many to campaign for suffrage. Bit by bit, they achieved local victories—stepping stones to full suffrage.

“To fill empty seats”

Women are clearly visible in this illustration of the crowd at the 1880 Republican National Convention in Chicago. Suffragist Susan B. Anthony complained that politicians—men—allowed women at conventions “to fill empty seats, wave handkerchiefs, and clap our hands when they say smart things.” But when women asked to participate in the political process by voting, men “push us aside and tell us not to bother them.”

The Business of Politics

The Palmer House was the site of committee headquarters, where party leaders planned strategy and negotiated deals during the 1880 Republican National Convention in Chicago. Without votes to give, women found themselves excluded as men went about the business of politics.

The So-Called "Natural" Order

Suffrage opponents included those concerned about disrupting the so-called “natural” order. Gender was typically viewed at the time in binary terms—men and women, each with different roles and responsibilities. Within the family, a man represented his wife and children with his vote. Women were supposed to be nurturing mothers, leaving the rough world of politics to men. Votes for women challenged this arrangement, threatening to undermine a society organized around these ideas about gender.

Elite white women, like Caroline Corbin and her Illinois Association Opposed to Woman Suffrage, believed women should not be “burdened” with voting. Instead, women contributed to politics by raising sons to be responsible voters.

Fearing Women's Power

While some suffrage opponents believed voting women upset the natural order of things, others feared women’s power at the ballot box.

Those who made and sold alcohol worried that women favoring prohibition would vote them out of business.

One Campaign at a Time

Although widespread support for a national suffrage amendment did not yet exist, by the late nineteenth century, some Western states had granted women full suffrage, and in cities such as Chicago, women gradually became voters one campaign and one law at a time.

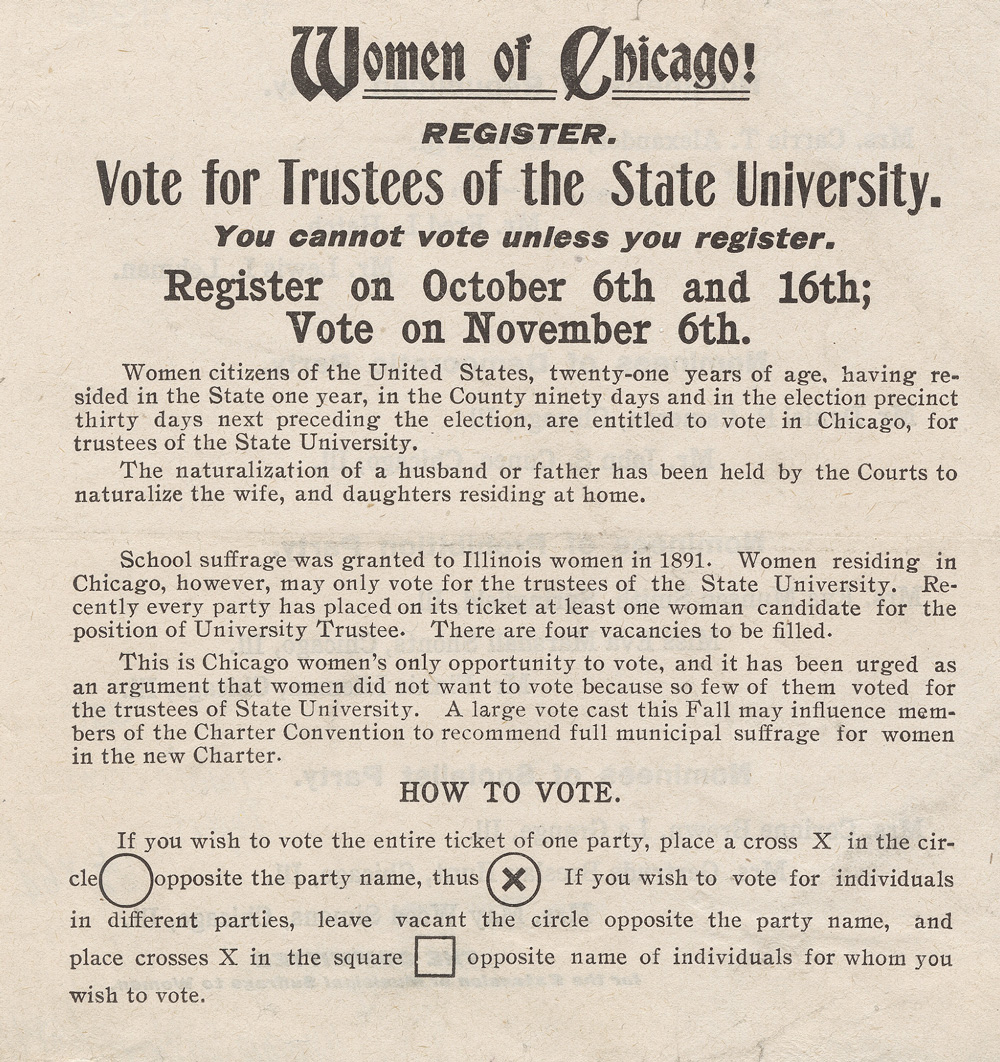

"Women of Chicago! Register."

Believing education fit within “women’s sphere,” Illinois lawmakers in 1891 allowed women to vote for school officials. In Chicago, where most school officials were appointed, not elected, women could now vote in one election—for members of the University of Illinois’s governing board. In the 1900s, activists began campaigning for “municipal suffrage” to allow Chicago women to vote for city officials. This flyer from around 1906 urged Chicago women to use their only vote to demonstrate desire for expanded voting rights.

Social and educational reform leader Lucy Flower (above) became the first woman elected to statewide office when women helped elect her to the University of Illinois Board of Trustees in 1894.

Why Women Should Vote

Hull House settlement founder Jane Addams gave this speech at a 1906 national suffrage convention. Such issues as housing, pollution, public health, and child welfare, she argued, were of special concern to women living in modern industrial cities.

Addams and others claimed a place for women in reform work by drawing on popular ideas about women’s identities as mothers and caregivers. Voting power, they argued, would help them get the job done. In the early 1900s, activists campaigned for Chicago women’s right to vote in city elections so they could be an even greater force in urban reform.

Reprinted in this pamphlet, Addams’s speech was easily and widely distributed as part of the “standard suffrage literature” of the national movement.

Statewide Suffrage Campaign

These suffragists are about to board a Springfield-bound train to lobby for a voting rights law. Campaigns for the vote in Chicago fueled a statewide drive for a law granting suffrage to Illinois women. In 1911, Illinois senators passed a nearly full suffrage bill, but activists could not win enough support in the House, where it was defeated.

Mrs. Florence M. Lorenz, Mrs. Ella S. Stewart, and Miss Bertha Seass, March 7, 1911, on their way to Springfield. They were part of a group traveling to the state capitol to urge lawmakers to support a state suffrage bill.

"Do You Approve...?"

“Do You Approve of Extending Suffrage to Women?”

On April 9, 1912, Chicago voters—men—were given the chance to answer this question. Hoping to convince lawmakers of widespread support for women’s suffrage, members of the Chicago Political Equality League managed to get the matter put before voters in a nonbinding poll. Despite women’s widespread campaigning, men answered no nearly two to one.

Activists did not give up. These groups of women built on relationships created during the campaign to continue fighting for a statewide suffrage law.

THE TELEPHONE BRIGADE

Grace Wilbur Trout (second from left), Illinois Equal Suffrage Association president, returned to Chicago after successfully lobbying to secure passage of a statewide suffrage law in 1913.

Trout and her team spent months in Springfield building support among lawmakers. They even organized a “telephone brigade.” When House speaker William B. McKinley returned home to Chicago the weekend before the final vote, he received phone calls every fifteen minutes from men and women expressing support for the proposed law.

“Why Do We Strive For Equality?”

In Chicago, immigrant women of many different backgrounds joined the struggle for the vote, participating in parades and rallies, selling suffrage pins, and appealing to fellow working-class men to support the cause.

Just weeks before passage of Illinois’s suffrage law, Glos Polek (Polish Women’s Voice) published in Chicago by the Polish Women’s Alliance of America asked, “Why Do We Strive For Equality?” This front-page essay challenged women’s secondary social and legal status and called upon men to support women’s demand for equal rights for the good of society.

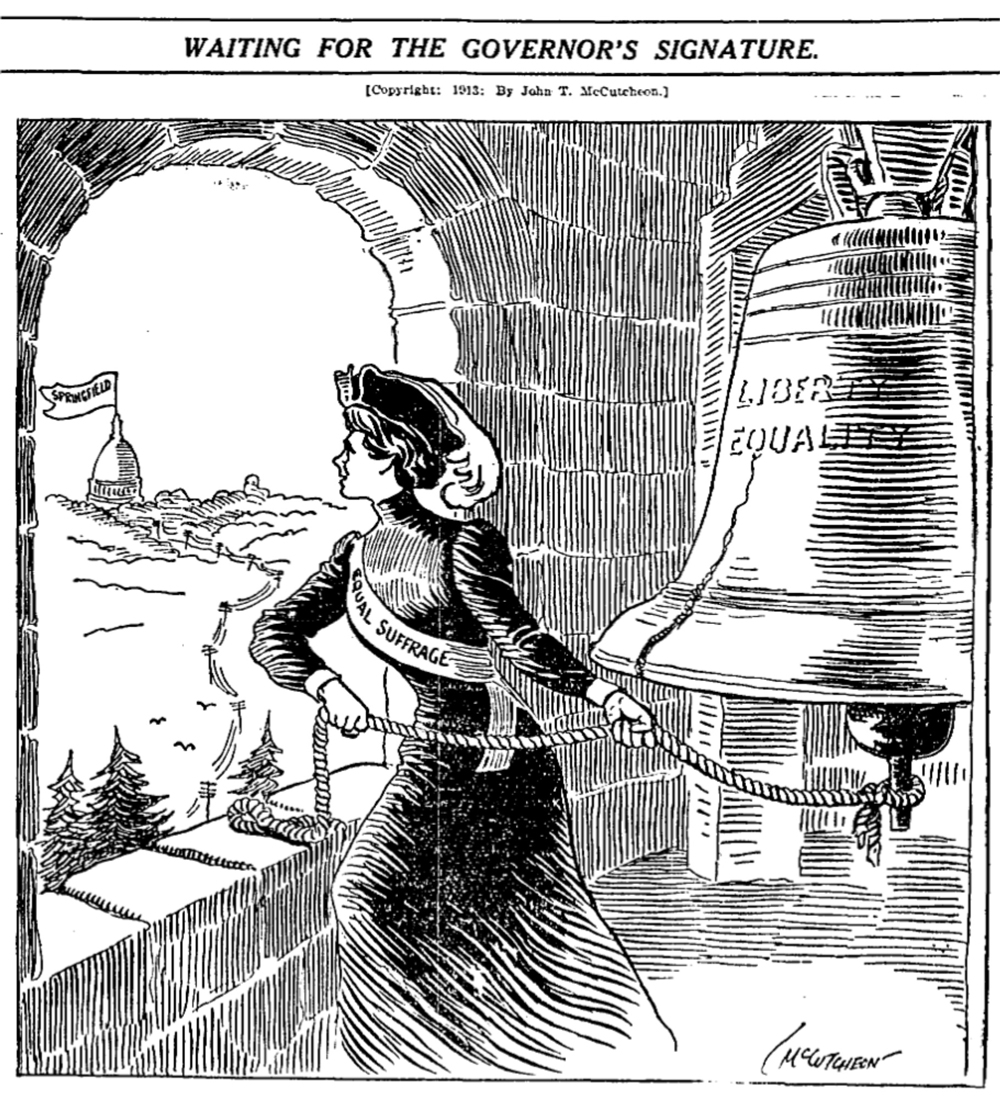

Illinois's Suffrage Law

This cartoon appeared in the Chicago Tribune on June 25, 1913, the day before Governor Edward F. Dunne signed the Presidential and Municipal Voting Act into law, empowering Illinois women to vote for local offices and in presidential elections.

After achieving passage of this law, Chicago women went to work registering voters and organizing to defend the law against legal challenges from those who continued to oppose it.

Wage Earners’ Suffrage League

Bootmaker and union leader Emma Steghagen created the Wage Earners’ Suffrage League (WESL) to organize Chicago Women’s Trade Union League members’ campaigning for the state suffrage law.

After its passage, labor organizers went to work “gathering in the girls for suffrage,” as Steghagen put it, urging participation in the WESL.

The WESL registered working women to vote so they could support labor legislation for shorter work hours and a living wage at the ballot box.

Within months of the state suffrage law’s passage, wage-earning women from twenty-two trades had joined the Wage Earners Suffrage League, including garment workers and glove makers, waitresses and stenographers, laundry workers and cigar box makers.

The group aimed to educate working women about labor and other political issues so their votes could “become a power in Illinois.”

ALPHA SUFFRAGE CLUB

Ida B. Wells-Barnett organized Illinois’s first Black women’s suffrage group in January 1913. Alpha Suffrage Club members such as club officer Sadie Lewis Adams (pictured) embraced voting rights granted by the 1913 suffrage law, canvassing Chicago’s Black wards to register voters. Their efforts to activate Black women’s voting power helped elect the city’s first Black alderman in 1915.

This victory for Chicago’s Black women voters drew warnings in the South through racist antisuffrage propaganda, where whites opposed a federal amendment that would empower both Black and white women voters.

Ella G. Berry

Before moving to Chicago from Kentucky, community activist Ella G. Berry witnessed southern Democrats’ creation of Jim Crow laws and efforts to prevent Black people from voting. This shaped her view of the importance of African Americans’ collective voting power and her support for Republican candidates, whose party in the past had used federal power to protect civil rights for African Americans in the South.

During 1916’s presidential election, Berry organized Black women statewide for Republican Charles E. Hughes, challenging Woodrow Wilson’s reelection bid. During his first term, Wilson presided over Jim Crow’s expansion in the federal government.

Berry was active in local politics. In 1914, she joined Chicago’s Second Ward Political Equality League to rally support for a Black independent Republican city council candidate.

"I March for Full Suffrage“

By 1913, Chicago women had achieved limited yet powerful voting rights.

That victory did not stop efforts to gain full suffrage, as suggested by this button promoting a June 1916 march in Chicago to demonstrate support for a federal voting rights amendment.