Votes for Women

Part of a Movement

By the early twentieth century, Chicago-area women’s struggle for the vote was part of a mass movement drawing increasing media attention. Suffragists claimed the vote as a matter of equal rights and a key to solving other problems and injustices. But many thought voting was a man’s job, and women endured laughter and insult, violence and jail, before a federal amendment was passed.

Along the way, women of different backgrounds stitched banners and marched in parades. Some gave speeches or wrote suffrage literature, while others handed it out in the streets. Still other Chicago women picketed the White House and went to prison for it.

In 1920, the Nineteenth Amendment to the US Constitution prohibited states from denying the right to vote “on account of sex.” This was an undeniable victory for activists who worked long and hard to achieve it. Yet, many still could not vote. And the task of overturning many forms of discrimination, inequality, and injustice remained unfinished.

The Spectacle of Suffrage

Suffragists staged events—dramatic marches, parades, automobile tours, performances—to grab headlines and provide striking images for photographers that filled daily newspapers by the 1910s. Here, a group poses for publicity photos before a July 1910 automobile tour of northern Illinois.

Grace Wilbur Trout (left), Belle Squire, S. Grace Nicholes, and Ella S. Stewart, photographed in front of Michigan Avenue’s Fine Arts Building, headquarters for the Illinois Equal Suffrage Association. As president of this group, Trout launched new tactics, including the auto tours, to promote suffrage.

"Motoring Militant Suffragettes"

In summer 1910, Chicago activists planned several auto tours to gain publicity and support for suffrage in Illinois. Suffragists crossed the state—traveling west to Galesburg, north to Waukegan, northwest to Rockford, and south to Champaign—in automobiles loaned by wealthy backers. As they pulled into each town along the way, a vocalist sang to draw a crowd and suffragists gave speeches and passed out pamphlets.

Tours attracted widespread press coverage. Some reporters called suffragists “militant” and “invaders” and wrote about what they wore on the trips. But tours also received favorable accounts and stirred support for suffrage.

The Chicago Tribune sent a reporter with suffragists on the first tour and later published essays by tour participant Belle Squire.

Parade Preparations

A suffragist prepares to parade down Michigan Avenue on May 2, 1914. The parade was planned to coincide with nationwide demonstrations urging Congress to pass a federal suffrage amendment.

The cotton hat seen here was created for a suffrage parade.

Banners like the one above carried by Chicagoan Alice Prince Miller, along with flags, costumes, and hats, added to the spectacle of the many suffrage parades of the 1910s.

Ida B. Wells protests

At the March 3, 1913, Woman’s Suffrage Procession in Washington, DC, Ida B. Wells-Barnett protested organizers’ insistence that she march separately with Black suffragists instead of with her white peers from Illinois.

That morning, Illinois Equal Suffrage Association president Grace Wilbur Trout had advised the Illinois women to go along with national leaders’ efforts to exclude Wells-Barnett. Wells-Barnett refused. Instead, as white suffragists from Illinois passed by, she joined Belle Squire and Virginia Brooks, who had opposed the plan to segregate Illinois suffragists, and marched alongside them.

Suffragist Alice Paul believed a spectacle would attract media attention and widen support for women’s voting rights. Knowing national support was required for a constitutional amendment and concerned that integrated marches would upset white southern suffragists, however, she and other parade planners tried to limit Black women’s participation.

Suffrage Plays

Set in the 1860s and based on women’s legal status at that time, this 1911 suffrage play by Catherine McCulloch tells a story of political awakening. In it, a group of middle-class women realizes that without voting power they cannot change laws harmful to themselves and the title character, Bridget, a laundry worker whose earnings, by law, are the property of her husband.

Suffragists wrote and performed plays to dramatize the need for the vote and raise money for their campaigns.

Laura Cornelius Kellogg

Growing media attention to the mass movement for suffrage included this article about Indigenous activist Laura Cornelius Kellogg, whose Oneida identity connected her to traditions of politically empowered women in the Haudenosaunee Confederacy.

Kellogg was a founder of the Society of American Indians, which worked for Native American rights. In 1920, she presented her book to the Chicago Historical Society, which challenged existing harmful federal policies and control over Native lands. Kellogg became an early advocate of taking legal action to enforce treaty rights to regain Native lands.

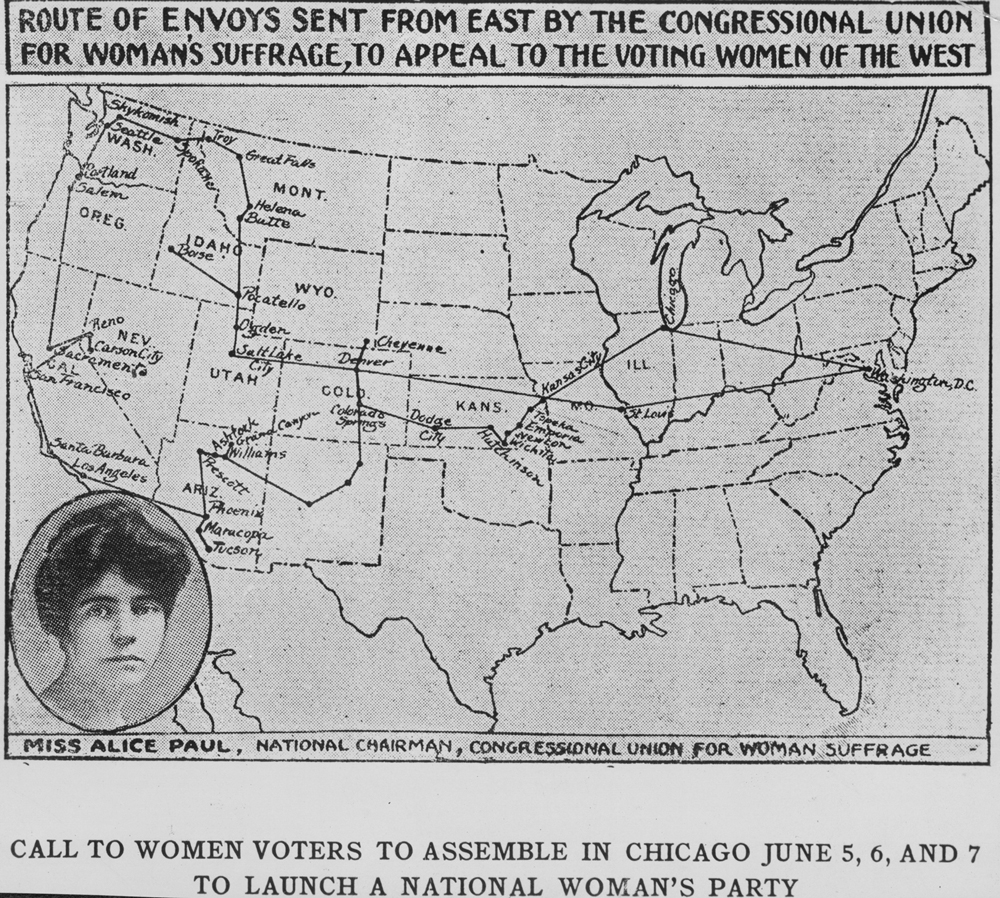

"To the Voting Women of the West"

In April 1916, Eastern suffragists made Chicago their first stop in a five-week campaign to encourage women in “suffrage states” to form a National Woman’s Party. Its goal: achieve a federal suffrage amendment.

In states like Illinois, where women could already vote for president and other offices, Alice Paul’s Congressional Union wanted women to use their votes to pressure candidates to support nationwide voting rights for women.

Inspired by British suffragettes’ militant tactics, Alice Paul formed the Congressional Union for Woman Suffrage (CU) in 1913. Disagreements over leadership and strategy split this group from the more moderate National American Woman Suffrage Association. In June 1916, the CU organized a convention in Chicago of women voters to form the National Woman’s Party.

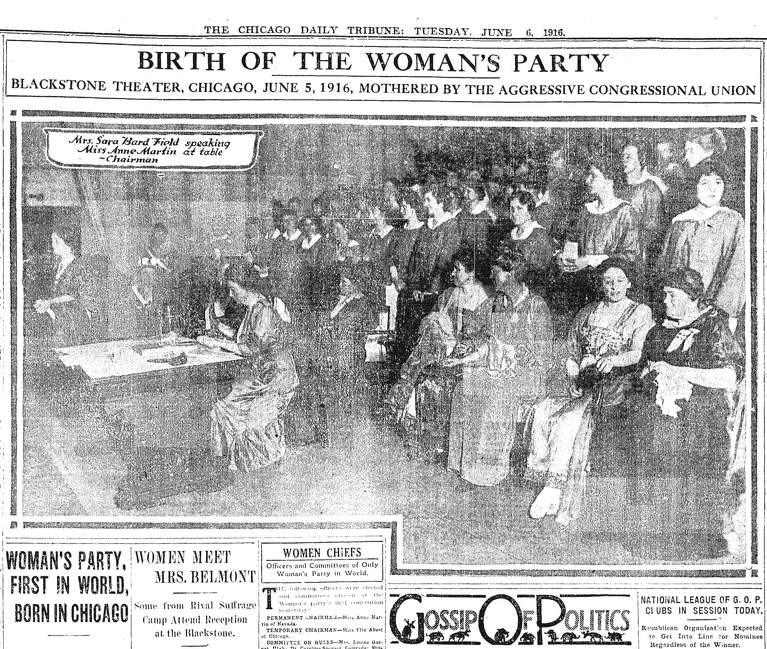

"Birth of the Woman's Party"

The creation of the National Woman’s Party caused controversy among suffragists in Chicago and beyond, drawing criticism from those concerned its aggressive tactics, such as picketing and protesting, would turn many against the movement.

Demonstrations Against Wilson

In keeping with its policy of “holding the party in power responsible” for failing to pass a suffrage amendment, National Woman’s Party members demonstrated against President Woodrow Wilson as he campaigned for reelection in Chicago. They were attacked by a mob of Wilson supporters. Below, a worker carries away splintered signs and wreckage.

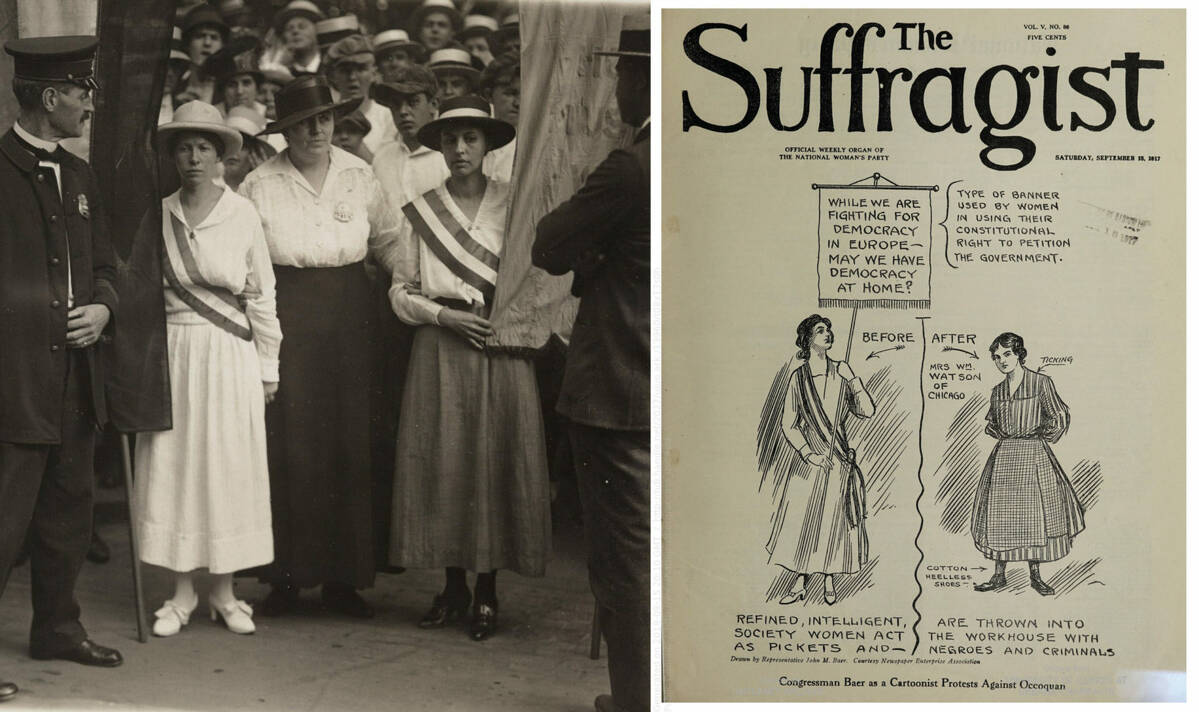

Sentenced for Picketing

After the US entered World War I, demonstrators protesting President Wilson’s failure to support a suffrage amendment faced frequent attack by angry mobs as well as arrest.

A Chicago sailor on duty in Washington, DC, tore this protest banner from suffragists, among them Madeline Upton Watson, during riots outside National Woman’s Party headquarters and the White House. Watson and fellow Chicagoan Lucy Ewing (pictured below) were among six women arrested on August 17, 1917, and sentenced to thirty days for picketing.

"Thrown into the Workhouse"

Meant to arouse sympathy for jailed suffragists, this cartoon offered a racist description of Watson as an “intelligent society woman” “thrown into the workhouse with negroes and criminals.” Drawn by Congressman John M. Baer, it appeared on the cover of the National Woman’s Party’s weekly newspaper.

Left: Chicagoan Madeline Upton Watson (right), before her arrest for picketing the White House.

"Prison Special"

National Woman’s Party members arrived in Chicago on March 5, 1919, to tell of their mistreatment, including being force-fed after launching a hunger strike while “jailed for freedom.” Suffragists toured the US on a train, nicknamed the “Democracy Limited,” to share their stories. Their ordeal helped gather the final support needed for passage of the Nineteenth Amendment.

The Nineteenth Amendment

“The right of citizens of the United States to vote shall not be denied or abridged by the United States or any state on account of sex.”

The Nineteenth Amendment was passed by Congress in June 1919. It was ratified and became part of the US Constitution in August 1920.

Educating Women Voters

After the Nineteenth Amendment’s ratification, the Woman’s City Club of Chicago in the 1920s offered citizenship classes, preparing women to educate women voters about city politics and elections. Even as these women embraced participation in the political process, however, many others remained excluded.

Boundaries of Inclusion and Exclusion

Although not always working side by side, Chicago women’s activism toward the common goal of voting rights crossed lines of race, class, and immigration status.

Yet laws that excluded some groups from citizenship prevented many people from voting, such as Asian immigrants and US women who married noncitizens. And just as racist ideas and tactics had shaped a nationwide battle for a women’s suffrage amendment, they continued to draw the boundaries of inclusion and exclusion when it came to determining who could vote.

Native Voting Rights

In the early 1920s, Zitkála-Šá, or Gertrude Simmons Bonnin (Yankton Sioux), addressed women’s clubs in Chicago and elsewhere about US citizenship and voting rights for Indigenous people.

Native peoples survived centuries of genocidal policies and practices at the hands of European and American colonizers. For Zitkála-Šá, citizenship and voting rights were keys to Native peoples’ ability to continue resisting damaging US policies and to fight for self-determination.

Congress extended US citizenship in 1924 to all Native people, regardless of their wishes. Zitkála-Šá welcomed this law and traveled widely to educate and register Native voters. Many states, however, passed restrictive laws that prevented Indigenous people from voting.

Continued Barriers

In 1968, Fannie Lou Hamer was seated as a Mississippi delegate to the Democratic National Convention in Chicago. The recognition came four years after she was denied the chance to represent her state’s Black voters as a member of the Mississippi Freedom Democratic Party, formed to challenge the state’s whites-only Democratic party.

Hamer was evicted from her home after trying to register to vote. During years of suffrage activism, she endured arrest, brutal beatings, and death threats.

The 1965 Voting Rights Act banned discriminatory barriers to voting long faced by Black voters like Hamer.

Yet decisions about who can vote and about the process for casting and counting ballots continue to place barriers before marginalized and vulnerable people, limiting who can partake in democracy.