VISIONARY WOMEN

Women of Hope, Vision, Action

In the decades after the Civil War, women of hope and vision made the Chicago area a center of activism. Women lacked rights, economic security, and formal political power. But they refused to accept this. Instead, women from different backgrounds spoke out against injustices, identified problems and organized to solve them, and challenged the status quo.

Creating change—for themselves, their families, and their communities—was no easy task. These activists had to change people’s minds about what a woman could, should, and had a right to do. Without formal political power, but fighting to achieve it, women formed organizations and alliances. They turned to the law. They took to the press, the podium, and the streets. They sought the vote.

Mary Richardson Jones

Before joining the movement to secure women’s right to vote, Mary Jones, a free Black woman, fought to end slavery. After moving with her husband to Chicago in 1845, she served as a “conductor,” opening her home to aid those fleeing slavery along the Underground Railroad. Jones assisted her husband’s decades-long campaign to end Illinois’s racially restrictive Black Codes. After the Civil War, she joined Chicago women in organizing for women’s suffrage and was later active in the city’s Black women’s club movement.

“The Agitator”

With women excluded from the political world, “a large portion of the nation’s work was badly done, or not done at all.”

Mary Livermore came to this realization while working for the US Sanitary Commission, which handled relief efforts during the Civil War. Determined to change things, in 1869, she headed a woman’s suffrage convention in Chicago and founded The Agitator. Its motto: “healthy agitation precedes all true reform.”

Male friends suggested calling this newspaper “The Lily” or some other “mild” name fit for a woman’s publication. Livermore insisted on the “The Agitator,” which conveyed fierce intent to stir people up and create change.

Naomi Bowman Talbert

In 1869, Talbert urged attendees at a Chicago women’s suffrage convention to support voting rights regardless of race or sex, but Talbert wasn’t always credited for her work. Suffragists Elizabeth Cady Stanton and Susan B. Anthony publicized her speech in their newspaper, The Revolution, but identified her only as “a colored woman.”

Talbert continued to write, speak, and take action for the rights of women and Black people. In Wichita, Kansas, in the 1880s, she founded an orphanage for Black children excluded from the whites-only children’s home. In the 1890s, she campaigned for suffrage, calling for “justice and . . . a voice in making the law” for women.

Home vs. Saloon

More than 200,000 women fought against alcohol abuse and domestic violence by joining the Woman’s Christian Temperance Union, headquartered after 1885 in Chicago and later, Evanston.

Early campaigners prayed for saloons to close their doors. But in 1879, Frances Willard and her supporters sought the vote as a matter of “home protection.” Women’s votes, they believed, would protect women and families by securing reforms such as laws prohibiting the sale of alcohol.

As WCTU president, Willard hoped to organize women nationwide. But in seeking support in the 1880s from Southern white women, Willard accepted segregation in WCTU chapters and failed to condemn lynching.

Myra Bradwell

Did a woman have a right to pursue her chosen occupation?

When Illinois courts said in 1870 Myra Bradwell could not practice law, the woman’s rights activist launched the first sex discrimination case heard by the US Supreme Court. She lost. One judge claimed woman’s “delicate nature” made her unfit for many jobs.

Barred from practicing but well-versed in the law, Bradwell published a successful law journal—Chicago Legal News—and found lawmakers to back legislation she drafted. She helped write the first law prohibiting employment discrimination. After participating in Chicago’s 1869 suffrage convention, she also drafted the Illinois law granting married women control of their earnings, which until then had belonged to their husbands.

The Black Women’s Club Movement

Black women facing the dual burden of racism and sexism did not have the luxury of battling only for women’s rights. Their longtime activism reached new heights in the early 1890s with the creation of a network of women’s clubs devoted to social action.

Many of the issues they addressed remain painfully familiar and unresolved—a racist criminal justice system, violent attacks on Black men and women intended to maintain racial oppression, exclusion from white institutions, economic disparities.

Chicago women played leadership roles in this national movement. Locally, they organized to meet the needs of their communities while addressing racial inequities both within the city and the nation.

Fannie Barrier Williams

Chicago’s Fannie Barrier Williams represented Illinois’s Black clubwomen at the Colored Woman’s Congress in Atlanta in 1895. To her, the women’s club movement was a “national uprising” of Black women “pledged to the serious work” of racial advancement. A skilled public speaker, journalist, and suffragist, she worked to meet the needs of Black Chicagoans excluded from the city’s white institutions.

Barrier Williams assisted in the creation of Provident Hospital, which provided health care to the city’s Black community. She also actively supported the Phyllis Wheatley Home for Girls. There, excluded from the white YWCA, young Black women relocating to Chicago found a safe residence, employment help, and other services.

National Association of Colored Women

Elizabeth Lindsay Davis joined Chicago clubwomen in hosting the 1899 meeting of the National Association of Colored Women, an umbrella organization of Black women’s clubs, at Quinn Chapel, a longtime political gathering place for the city’s Black community.

Participants addressed topics traditionally linked to women’s roles as caretakers or moral guardians of the home. They also focused on urgent, life-and-death matters for Black people: lynching, segregation, and the convict-lease system—forced prison labor that targeted African American men.

As NACW national organizer and historian, Davis greatly expanded its membership and documented Black activist women’s vital work.

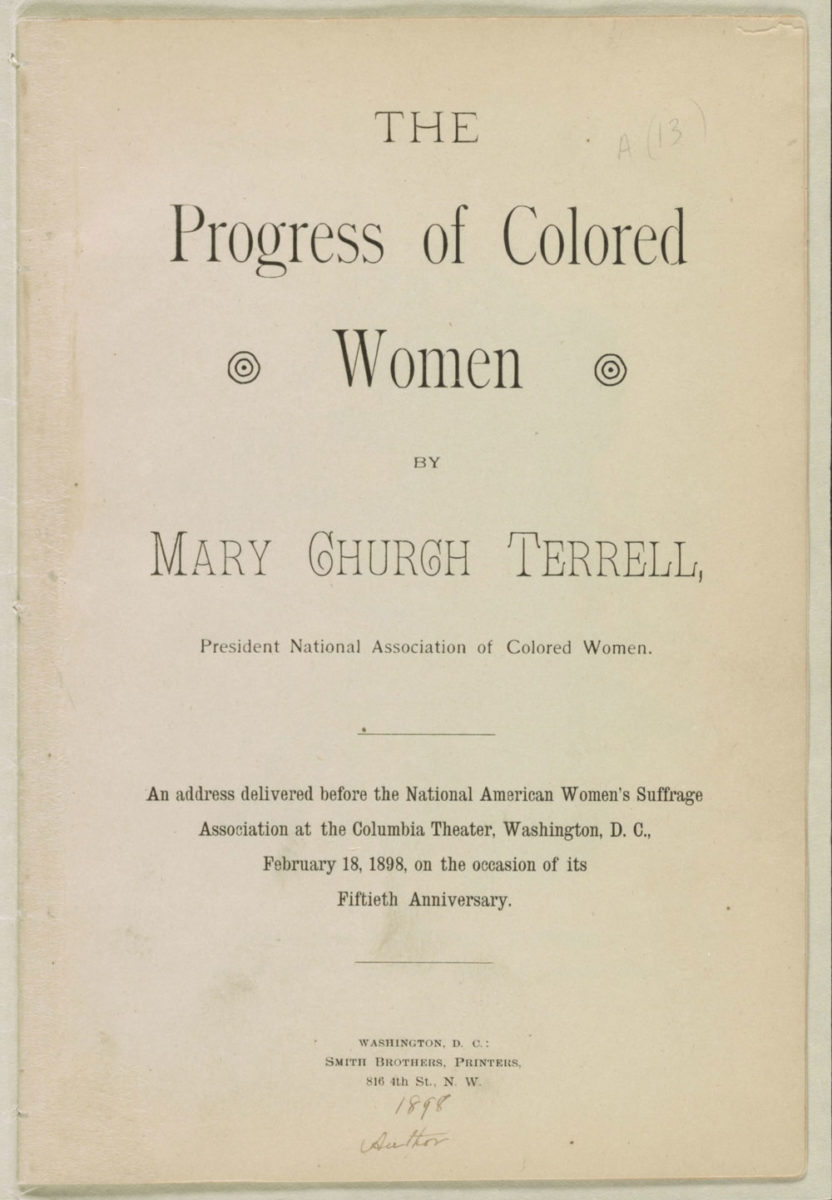

“The Progress of Colored Women”

Copies of this speech sold for ten cents at the 1899 Chicago meeting of the National Association of Colored Women, to raise money for a kindergarten. A founder and first president of the NACW, Mary Church Terrell spent her life fighting for racial justice. She organized and spoke out against lynching, segregation, and disenfranchisement.

Mary Church Terrell gave this speech (left) at the National American Woman Suffrage Association convention in February 1898.

"Loyalty to Women and Justice to Children"

The Illinois Federation of Colored Women’s Clubs was created in 1899 by the joining of the “Magic Seven”—Chicago’s first Black women’s clubs. The federation’s motto: “Loyalty to Women and Justice to Children.” Although the women pictured here lacked full suffrage until 1920, they enacted democracy as voters and office holders within their club work.

Elizabeth Lindsay Davis served as president and historian of the state federation. These portraits (below) were published in her book, The Story of the Illinois Federation of Colored Women’s Clubs, 1900–1922.

Urban Reform

In the growing industrial city, middle-class reformers promoted child welfare by campaigning to end child labor and make school mandatory. For these women, advocating for the safety and well-being of the city’s children, workers, and other residents was made more difficult without the vote. They wanted laws passed and enforced to improve such things as education, workplaces, and housing, but lawmakers and officials did not feel they had to answer to women who could not vote for them.

The Slow Work of Persuasion

“It would make a vast difference if women in American cities could enforce their will and conscience by the ballot instead of by the indefinitely slow work of persuasion.”

— Florence Kelley, social reformer, anti-sweatshop campaigner, Illinois’s first Chief Factory Inspector