Underpaid, Undervalued

A long fight for workplace fairness

Amid the struggle to secure women’s voting rights, women worked for wages to support themselves or their families. Yet, many earned barely enough to get by. The expectation that a woman would be financially supported by a man helped employers justify paying them so little.

In Chicago’s factories, shops, restaurants, and laundries, women endured long hours, harsh conditions, and seasonal layoffs. Some walked picket lines in the bitter cold to protest their poor treatment, only to be hauled away by hired guards or police.

Labor activists and their allies lobbied for laws to protect working women’s health and safety. They protested police brutality against “girl strikers.” They fought for equal pay and limits on work hours. They organized unions, believing group action would bring more power to wage-earning women. These women saw the vote as a tool to help working women create an “industrial democracy.”

Since then, economic transformations have changed the nature of many jobs, but not the underpayment and undervaluing of women. Their long fight for workplace fairness and economic justice continues.

“Behind suffrage is the demand for equal pay for equal work.” –Leonora O’Reilly, labor activist

Walking off the job

In September 1910, young women walked off the job at clothing maker Hart Schaffner & Marx to protest wage cuts and unfair working conditions. Their action sparked a months-long strike of more than 40,000 garment workers, half of them women, including many recent immigrants from southern and eastern Europe.

Under Arrest

Police arrested this woman and many others during the massive garment strike in 1910. Labor activists and their allies protested the arrest and harsh treatment of peaceful picketers, including the use of private police forces against striking workers.

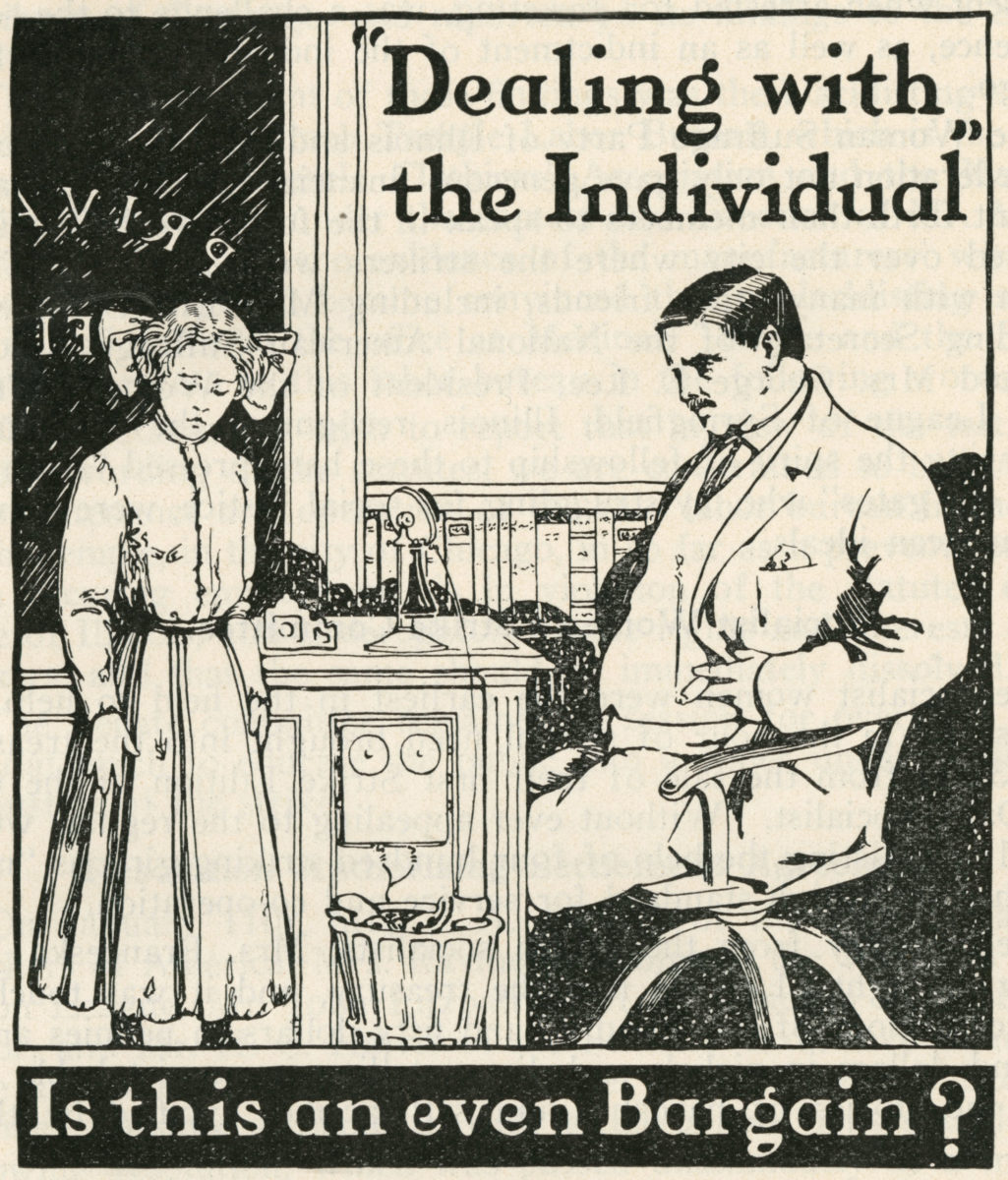

"Is this an even bargain?"

During the 1910–11 garment workers’ strike, this widely circulated cartoon highlighted an important demand—the right to organize and bargain as a group with employers. One report issued by supporters called it “absurd that a girl of sixteen years should be left to bargain as an individual with a . . . powerful firm.”

When Illinois women achieved partial voting rights in 1913, strike leader Bessie Abramowitz, an immigrant from Russia, and three thousand garment workers joined the Wage Earners Suffrage League.

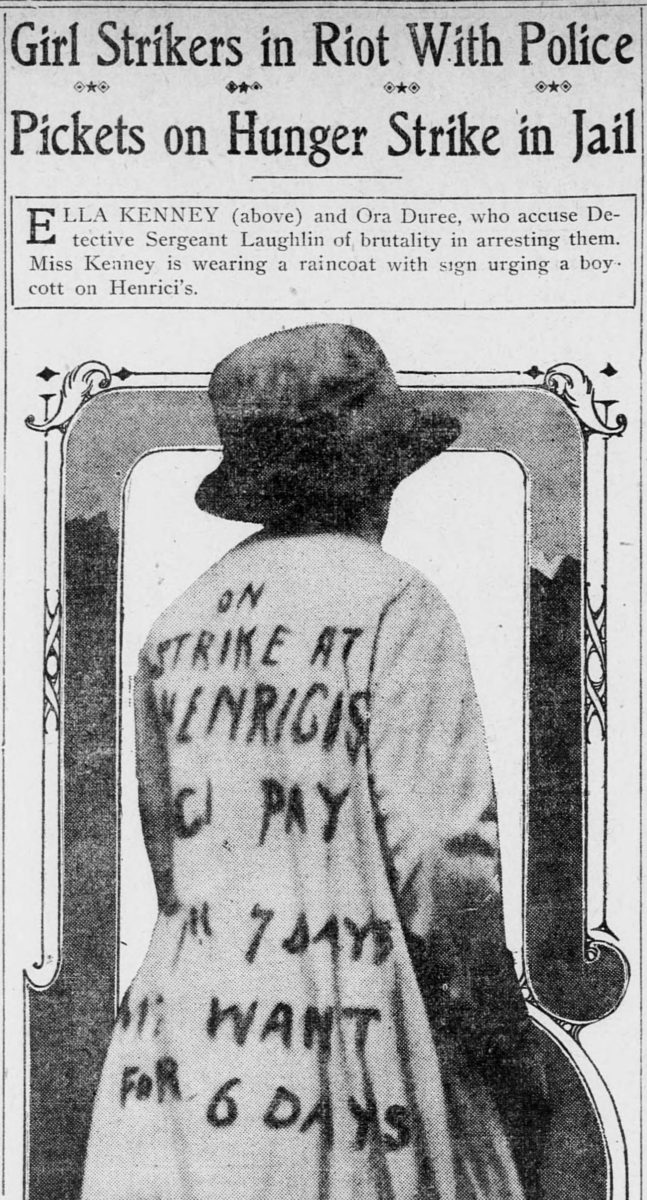

“GIRL STRIKERS”

In February 1914, four waitresses marched through a lunchtime crowd outside a Randolph Street restaurant wearing coats painted with their demands: “Strike on at Henrici’s. Henrici’s pays $7 for 7 days. We want $8 for 6 days.”

When police tried to arrest them, the “girl strikers” sat down and refused to go without a fight. They were later charged with encouraging an illegal boycott. These waitresses and other restaurant workers wanted a living wage and better workplace conditions. They faced opposition from restaurant owners and police, who often sided with businesses during workers’ strikes.

Four hundred unionized waitresses joined the Wage Earners Suffrage League in 1913.

ELLEN GATES STARR

Ellen Gates Starr, a middle-class social reformer, was arrested on disorderly conduct charges after protesting the arrest of striking waitresses outside Henrici’s Restaurant. As co-founder of Hull House, Starr saw first-hand the poverty and unjust treatment of the city’s laborers, prompting her activism for worker’s rights, especially women. Like Starr, other middle-class Chicago women raised money for striking workers, bailed them out of jail, joined picket lines, and faced arrest.

"The Girls Who Did the Work"

This pamphlet published by the Chicago Women’s Trade Union League (WTUL) told the story of labor activists’ battle for a law limiting work hours for women in many jobs.

In the early 1900s, labor organizers such as Agnes Nestor and the WTUL urged wage-earning women to find strength in numbers by joining unions. They fought for higher pay and better workplace conditions, including a shorter workday.

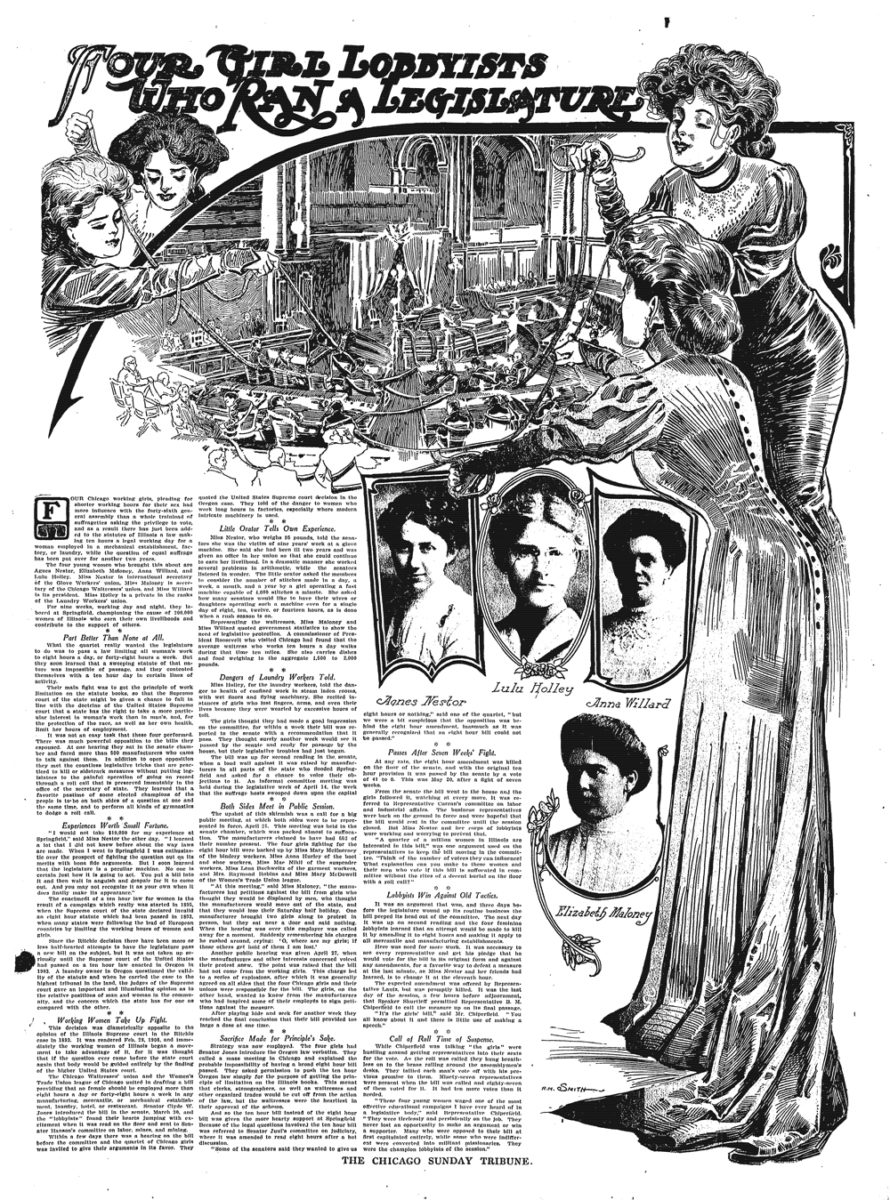

“FOUR GIRL LOBBYISTS”

This July 1909 newspaper account showed labor activists pulling the strings of puppet-like lawmakers. Agnes Nestor, Lulu Holley, Anna Willard, and Elizabeth Maloney made headlines as they tried to persuade the Illinois General Assembly to create a law limiting work hours to eight hours a day for women in many jobs where hours where hours were not restricted. They were not as powerful as this cartoon suggested. Facing strong opposition from manufacturers, they had to settle for a ten-hour law, calling the victory a step “in the splendid struggle for justice” for working women.

Their goals in Springfield were not limited to labor laws. As Chicago women pressed for municipal voting rights in 1909, Maloney and Nestor lobbied lawmakers for suffrage on behalf of working women.

IRENE GOINS

A leader in the Black women’s club movement, Chicago Women’s Trade Union League, and League of Women Voters, Irene Goins campaigned for workers’ rights and organized Black women stockyard workers during and after World War I.

Black wage-earning women faced the double burden of sexism and racism. Due to discrimination by white-owned factories and shops, Black women in early twentieth-century Chicago most frequently found domestic work—cooking, cleaning, and laundering—often in private households. The unsteady work in isolated private homes made it difficult for domestic workers to organize.

"The WORKING GIRL’S NEED"

“To us it is not a question of equal rights but a question of equal needs.”

To Agnes Nestor, former glove maker, union organizer, and longtime president of the Chicago Women’s Trade Union League, the “working girl” needed the vote just as all workers did. Nestor spent years lobbying for laws to protect workers. She claimed the ballot was necessary to secure health and safety laws and to improve conditions for wage-earning women.

Ongoing workplace and economic inequality

The vote gave women the ability to express their political will. But it did not change attitudes toward women or the circumstances they faced on the job: Barriers to training, employment, and advancement. Getting paid less than men. Sexual harassment.

In today’s economy, women are more likely to work in low-wage, insecure jobs, and to face the choice between a paycheck and time off to care for themselves or family members. COVID-19’s economic impact has only worsened such gender imbalances. Service industries, which employ many women, have been hard hit by the pandemic. And women have lost jobs or been forced to leave the workforce due to the demands of caregiving.

Many continue to lack workplace protections against discrimination and unfair or abusive treatment. Such inequities may intersect with discrimination based on race, immigration status, sexual orientation, gender expression, and disability to deepen workplace and economic inequality.

Addie L. Wyatt

Reverend Addie L. Wyatt addressed working women at the March 1974 formation of the Coalition of Labor Union Women (CLUW) in Chicago. CLUW sought to organize and empower women in the labor movement, advance workplace fairness, and ensure working women’s voices in the political process.

Wyatt battled intersecting gender, racial, and economic injustices throughout her life. She campaigned for Black voting rights in the South and fair housing in Chicago. As a union leader, she fought racial and gender-based workplace discrimination and supported the Equal Rights Amendment, which, if ratified, would have provided a constitutional guarantee for gender equality. It was narrowly defeated in 1982.

Chicago Women in Trades

Sexist ideas about women’s roles and abilities and gendered barriers to training and apprenticeship programs have long kept women out of many high-paying skilled jobs. In the 1970s, women entered construction trades such as carpentry, welding, or plumbing—jobs almost always held by men.

Chicago tradeswomen began meeting to help one another cope with the hostility and discrimination they faced in these male-dominated industries. The informal group became Chicago Women in Trades. It continues to provide training, support, and advocacy for women’s employment and advancement in trades and other nontraditional jobs.

Women install drywall during a Chicago Women in Trades training program.

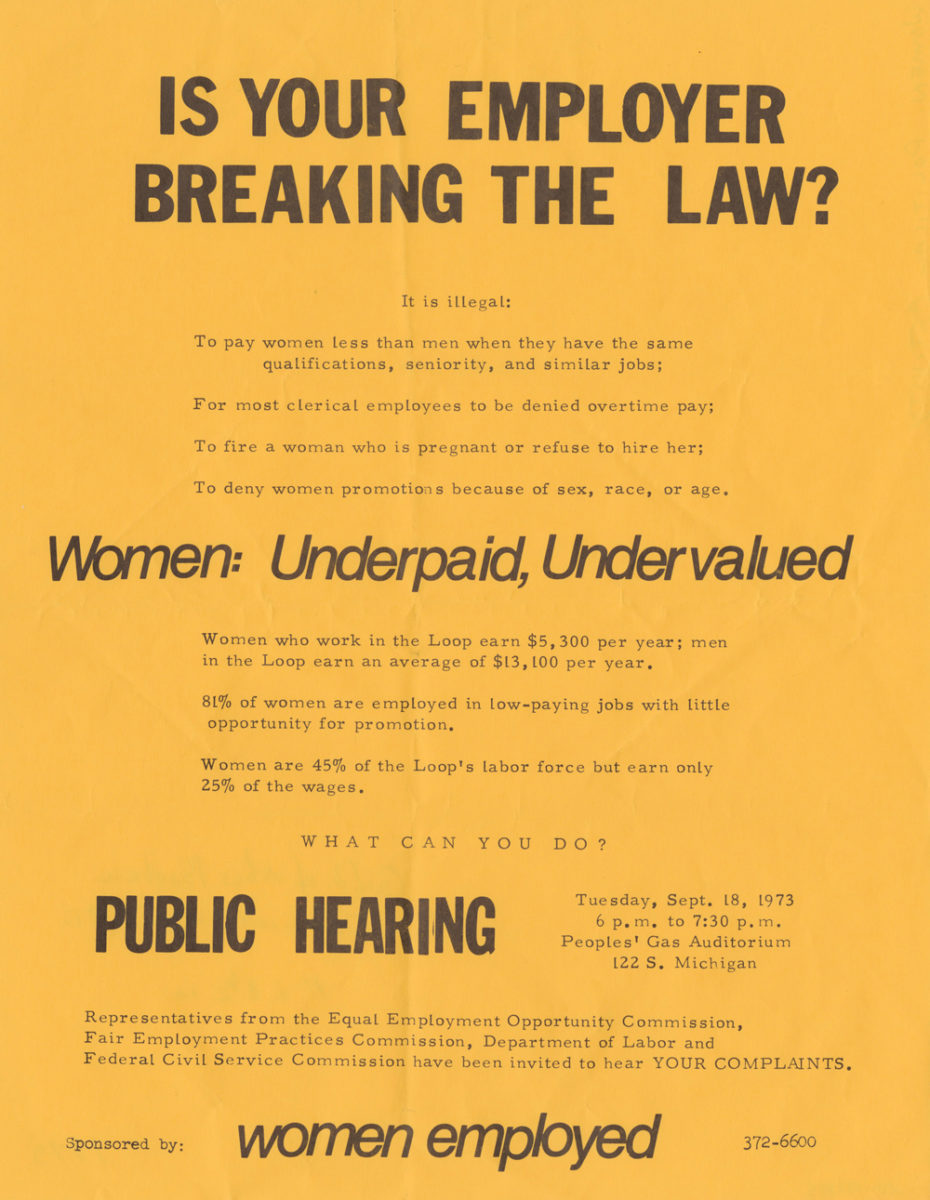

Breaking the law

Calling attention to pregnancy discrimination, the gender pay gap, and the concentration of women in low-paying jobs with little advancement, this flyer encouraged women to voice complaints about workplace injustices at a public hearing in downtown Chicago in September 1973.

Nearly fifty years later, the group that sponsored this hearing, Women Employed, continues to battle for these and other issues. In 2019 they advocated successfully for Illinois’s “No Salary History” law. It bars employers from asking job applicants or previous employers about past wages or salary. Since women typically earn less than men, the practice of basing pay on past earnings has contributed to the gender pay gap.

FIGHT FOR $15

Employees and union activists protest low wages outside a Chicago Whole Foods Market store in July 2013. In search of a living wage and worker protections, fast food and retail workers were participating in the “Fight for $15” campaign to raise the state’s minimum wage to $15 an hour.

Activists achieved a victory when Illinois lawmakers in February 2019 passed a law gradually increasing the state’s minimum wage to $15 an hour by 2025.

Fair paying, safe jobs

Activists and union members marked International Women’s Day on March 8, 2018, with a rally calling for fair paying, safe jobs. Women janitors of Local 1 of the Service Employees International Union took part in the demonstration amid contract negotiations with Chicago area employers.