ORGANIZE! TAKE ACTION!

UNFINISHED

Activists followed many paths into a mass movement for voting rights. In campaigns for social reforms, women’s rights, workplace fairness, and an end to racial oppression, organizing and action by women from different backgrounds began well before—and continued long after—the fight for suffrage.

Today, activist women continue to speak out against injustice, identify problems and organize to solve them, and challenge the status quo. They fight for fairness and inclusion. They create spaces that affirm identity and empower people. And they strive to respect the language, social, and cultural needs of communities while doing so.

The images that follow highlight just some of the ways Chicago-area women in the recent past and today have organized and taken action to create a more just and inclusive society.

PEARL M. HART

Throughout six decades of legal practice, Hart combatted injustice, defended civil liberties, and fought for the rights of marginalized people.

In the 1920s and ’30s, Hart served as a public defender for children and women in the county’s juvenile and women’s courts. During the mid-century anti-communist Red Scare, Hart appeared in behalf of many individuals called before the House Un-American Activities Committee. She also cofounded organizations opposed to repressive laws that targeted immigrants and leftists.

Hart also defended LGBTQ people victimized by police entrapment and harassment and was a founder in 1965 of the Mattachine Society of Chicago, an early LGBTQ-rights group. Hart served as the group’s legal counsel until her death in 1975 and was remembered as the “Guardian Angel of Chicago’s gay community.”

Guadalupe A. Reyes

The lack of existing resources for her child with developmental disabilities prompted Reyes to take action in ways that extended well beyond her own family. In 1969, Reyes founded Esperanza School for children with disabilities whose learning needs went unmet in traditional classrooms. In 1973, she founded El Valor, Illinois’s first bilingual and bicultural rehabilitation center. Both organizations continue to promote inclusion by providing education, programs, and supports for low-income families and people with disabilities.

Reyes was a leader in the Pilsen Neighbors Community Council, a grassroots group addressing issues from education to employment, housing to healthcare. During the 1970s, PNCC and activists like Reyes demanded creation of a local high school responsive to community needs. Galvanizing residents, their long battle resulted in Benito Juarez Community Academy, opened in 1977. To celebrate their success in pressing the Chicago Board of Education to build the school, Reyes organized a street festival in August 1974. That event became Pilsen’s annual Fiesta del Sol.

Marca Bristo

An internationally recognized force in the disability community, Bristo worked tirelessly to promote disability rights and to drive sweeping social reforms that changed Chicago and the nation. As the founding CEO of Chicago-based Access Living, a disability service and advocacy center for people with disabilities, run and led by people with disabilities, Bristo was committed to building a more inclusive society for disabled people to live fully engaged, self-directed lives. Access Living continues this work today.

In the 1980s, Access Living, Chicago ADAPT, and other demonstrators launched a campaign for accessible transportation, petitioning the Chicago Transit Authority (CTA) for lifts on public buses. Their activism and resulting lawsuit led to the improved accessibility of Chicago’s public transit, and created a blueprint for accessible transit systems across the country. Bristo then helped author the landmark 1990 Americans with Disabilities Act and fought fiercely for its passage.

CAROL WARRINGTON

What if your building owner wouldn’t fix your apartment? Carol Warrington (Menominee) refused to pay rent in protest of conditions in her rundown building. In May 1970, she was evicted. In response, she set up camp with her children outside 3717 N. Seminary Avenue. This prompted the creation of Chicago Indian Village, an encampment of dozens of supportive Native people, and launched a two-year protest drawing attention to the need for decent housing, education, and social services for Chicago-area Native people.

In the 1950s, the US ended its recognition of many Native nations and pressured Indigenous people to relocate from reservations to cities. These policies were yet another attack on Native communities and cultures. Thousands migrated to Chicago, where, like Warrington, they found little of the promised assistance.

Warrington at Lincoln Park Zoo, November 30, 1971, where she held a demonstration to highlight the poor housing conditions for many Native people in the city.

Diane Latiker

In 2003, Diane Latiker invited nine of her daughter’s friends into her living room to talk about what was going on in their lives. Sensing their need for guidance, compassion, and a safe place to hang out, Latiker opened her home, providing a refuge for teens in a community troubled by disinvestment, poverty, violence, and a lack of jobs and other opportunities.

Latiker’s initial welcoming gesture became Kids Off the Block (KOB), a nonprofit organization in the far South Side neighborhood of Roseland. Through Latiker’s tireless efforts, KOB has provided mentoring, educational opportunities, and recreational activities for thousands of at-risk, low-income youths.

In 2007, Latiker erected a memorial tribute to young people killed by gun violence. The initial display of seven stones has grown to include more than 700.

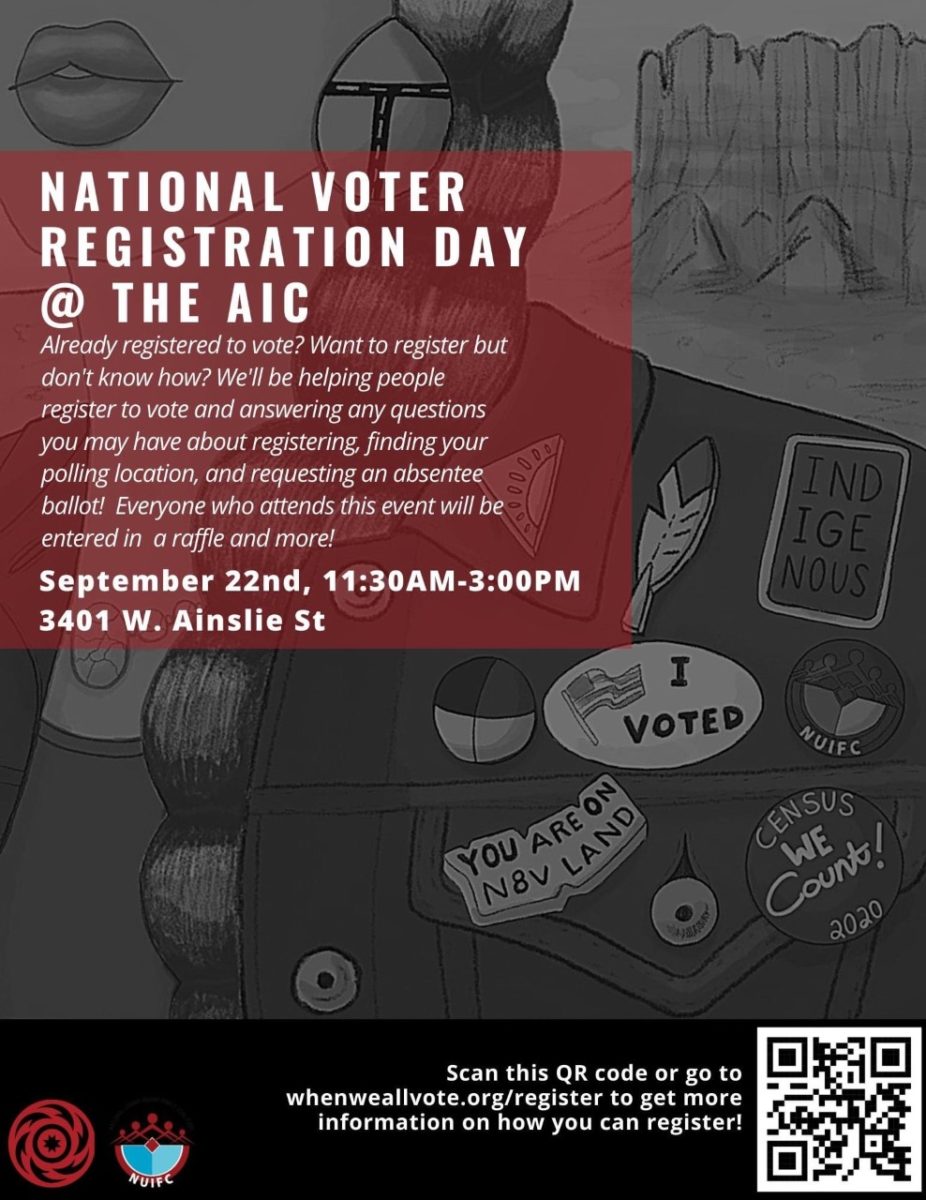

AMERICAN INDIAN CENTER

The September 2020 voter registration drive (pictured) held by Chicago’s American Indian Center (AIC) in Albany Park on the Northwest Side was part of wider efforts to mobilize the political power of Chicago’s Native community.

Susan Kelly Power and Josephine Fox were founding members of Chicago’s AIC in 1953. US policy makers who pressured Indigenous people to leave reservations for cities at mid-century expected them to lose their Native identities and blend into urban society. Defying these intentions, AIC supported Native identity and community in Chicago.

Through efforts like those of cofounder Angeline De Corah, who shared Native traditions with young people in after-school programs, and member Chauncina Yellow Robe Whitehorse, an advocate for Chicago’s Native elderly, AIC became an important cultural hub and service provider. Today, AIC remains a center for Indigenous culture, education, and activism serving thousands of Native people representing about 175 tribal groups.

Carmen Velásquez

Carmen Velásquez understood how language and cultural barriers along with concerns about insurance or immigration status kept many people in the Pilsen, Little Village, and Back of the Yards communities in the city’s West and Southwest Sides from accessing health care. In the 1980s, she became the driving force behind Project Alivio. The community campaign raised funds and support to create a medical center at 2355 S. Western Ave.

The bilingual/bicultural Alivio Medical Center opened in 1989 with Velásquez as the first executive director. It continues to operate an urgent care center and six community health centers, providing care for the un- and underinsured.